Is Creating a Common Ontology for Human History Feasible?

The world we live in today is a deeply interconnected reality, built on vast networks through which our information continuously flows. All the digital material we access daily is structured and organized through ontologies.

Ontologies are formal representations of a domain of interest. Thanks to this kind of organization, the Semantic Web — also known as Web 3.0 — is able to structure and analyze data, placing it within a network so that we can access it online.Today’s web is designed so that every piece of data is linked to others via its URI (Uniform Resource Identifier). The World Wide Web is the result of a radical way of thinking about the transmission of shared information — a vision more evident now than ever before. We use ontologies to model unstructured information or to connect the description of a set of things. These “things” can share information with other entities or highlight their differences.

But what about history? Could human history be organized in a global ontology?

Imagine organizing all the events that ever happened to humans into a collection of interconnected data. It would be revolutionary. Conceptually, as with any kind of data, creating a common ontology for human history is feasible. But practically, it’s incredibly challenging.

Why? Because when we think about the narrative of human history, it may seem straightforward — it’s nicely organized in the history books we studied at school. But the reality is, those books don’t represent the history of humankind as a whole— they often reflect a Eurocentric interpretation of global events.

Creating a common ontology for human history could offer us a realistic and inclusive structure of historical events. It could enable dialogues between nations that have never truly communicated. It could give voice to those who have never had the chance to share their truths. By incorporating multiple perspectives of reality, we might even come to understand that progress isn’t always tied to money or power — sometimes, it lies in simplicity.

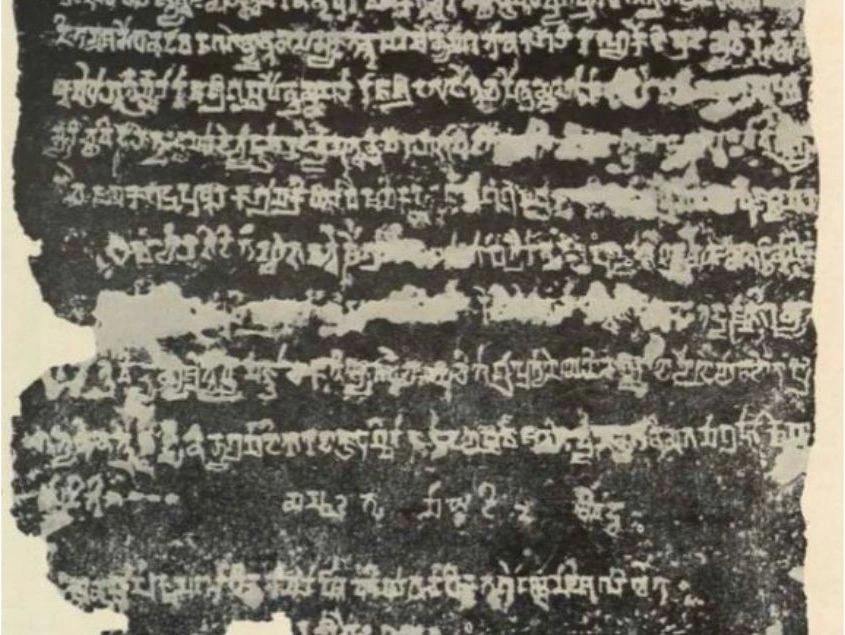

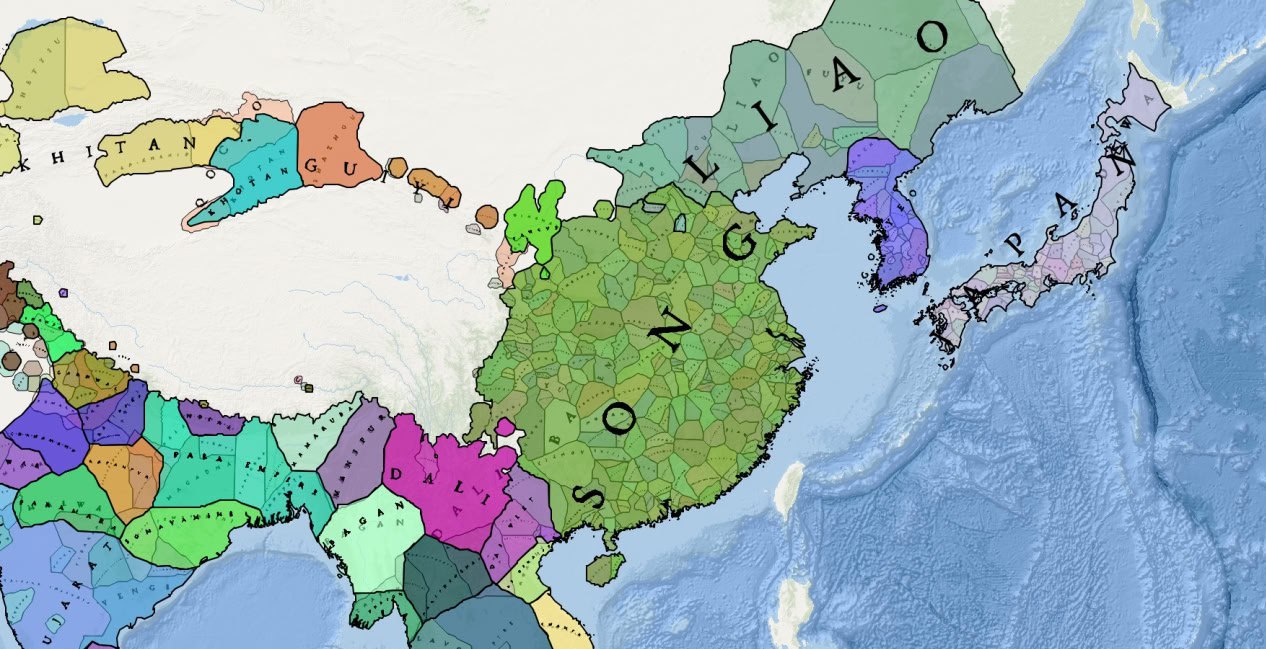

However, if we ever truly consider building a comprehensive historical ontology, let’s be honest — it would be an incredibly difficult task. To make it work, we’d need the entire world to collaborate. The complexity of the world is immense. Just look at the diversity of historical narratives: those told by the victors and those of people who still see their countries as victims of colonization. The data we need isn’t static — it changes case by case. It also shifts depending on the culture in question. So how can we build a single version of something that might have multiple meanings for different people?

Many cultures live in harmony with nature. Some still practice bartering. I could list countless examples, but the point remains: reality is relative.

Diversity is inherently subjective. We perceive reality through cultural lenses, which is not particularly helpful when working with domains that require objectivity. And then there’s the passage of time — the way we view events can change drastically. Take the Suffragette Movement as an example: once seen as rebellious and disruptive,suffragettes are now viewed as brave revolutionaries fighting for women’s rights.

The line is thin — and it’s not the only one. The interpretation of a single event can change from one country to another, or even within the same country. Politics can’t be separated from this process. We must acknowledge that many nations still practice censorship to control public narratives. Some historical events remain taboo even today. And yet, to faithfully organize history, every single event matters, something seemingly minor could have sparked major consequences.

A project like this would require collaboration not only from historians, but also philosophers, sociologists, mediators, and countless others — essential voices in gathering the necessary information to complete such a mission. Collaboration is vital not just because it enriches any research project, but because many short-term historical events are still being investigated and understood.

Personally, I remain deeply skeptical that countries will ever fully humble themselves to make amends for the many horrors and injustices for which they are, in some way, responsible.

Common Frameworks and AI

To promote collaboration, we could use semantic ontology tools and frameworks like OWL (Web Ontology Language), RDF (Resource Description Framework), or CIDOC CRM (Conceptual Reference Model). These tools could help define international standards. With standardized models, updating the ontology over time would be more manageable.

Given the complexity of each nation’s unique context, we would likely need to build sub-ontologies — smaller branches of the larger structure. These could focus on regions, historical periods, or specific cultural contexts, enriching the global ontology node by node. Artificial Intelligence could also support the process — identifying patterns and relationships between events, exploring historical timelines from multiple perspectives. Large Language Models (LLMs) could be trained on accurate and inclusive data, helping to construct more nuanced and well-rounded interpretations.

Still, even with all these tools, building such an ontology would be nearly impossible. Capturing every relationship would involve tough decisions — ones that might lead to exclusions. These omissions could introduce new biases, especially if the ontology is perceived as globally accepted and practically omniscient.

Conclusion

In the end, a common ontology for human history is theoretically achievable — if we learn to manage subjectivity, embrace diversity, and secure global collaboration on data retrieval and structuring. Such a project would be revolutionary — a testament to cooperation, understanding, and objectivity.

Yet, I firmly believe this challenge will remain unfulfilled. Because the privileged man is rarely willing to admit the bluff behind the narrative he has been feeding others —or worse, to admit that the version of reality we’ve accepted is not the only one, but merely one of many.