Artificial intelligence and Indian Epigraphy: Problems and Promises

Introduction

Artificial intelligence is a potent instrument that has incessantly helped mankind since its inception and interdisciplinary integration, felicitously accomplishing several daunting enterprises. From exploring minerals and biomes in the unfathomable depths of the Earth to unlocking complex, hitherto untouched areas of the limbic system, the technological magic and prowess of A.I. have and would definitely continue to reign high. A.I. has successfully integrated with different disciplines with varying degrees of success.

In history, A.I. helps in cross-connecting multidimensional data, though not in generating facts, which remain in the hands of researchers, as crafting novel facts requires newer sources, as offered by numismatics, epigraphy, etc. However, this scenario is now witnessing a radical change. An enterprising example comes from epigraphy: Google DeepMind has recently developed Aeneas, a cutting-edge technology which can ‘read’ fragmented, weathered, and effaced epigraphical records. While its promises seem tempting, the international community seems apprehensive. A question that is oft-invoked: Would Aeneas, or, for that matter, artificial intelligence, be a gift for historians and educationists, or an instrument of apocalypse? Here, we would try to comprehend the contours of this question to reach some definite ground.

Pythia, Ithaca, and Aeneas: The Rise of Artificial Intelligence

Understanding the impact of artificial intelligence in epigraphical studies necessitates a short and succinct explanation about its design. Aeneas, the latest generative software, builds upon past models of Pythia, a textual reconstruction software that, through its multifaceted neural networks, efficiently performs character- and word-level analysis, and hypothetically ‘restores’ missing texts, and Ithaca (2022), an advanced version of Pythia that introduced geographical and cultural particularities into the algorithm.

The previous two models are not generative but rather indicative; in other words, while Pythia only restores missing and damaged text, it does not do so out of the blue but utilizes common graphical methods. Ithaca only provisions cultural features based on geographical data fed into the system. It is with Aeneas that the game undergoes a complete overhaul. Assael et al. co-developed Aeneas with the University of Nottingham, in partnership with researchers at the Universities of Warwick, Oxford, and Athens University of Economics and Business (AUEB), exploring how generative A.I. could help historians solve unanswered questions.

Aeneas is presented as a multimodal neural network that uses inscriptional images and texts as inputs, which are then processed by a transformer-device decoder by retrieving similar datasets from closest parallels, called ‘embeddings’. The setup works on deep learning to develop single machine-actionable inputs, which contextually infer how the concerned inscription relates to others of its kind. Then, Aeneas works on a multimodal level to not just restore lost and damaged parts of inscriptions, but also generates historically grounded contextual outputs—inscriptional parallels, provenance, and chronological dating—thereby producing a hypothetical conjecture that seems as truth itself.

Artificial Intelligence and Indian Epigraphy: Conundrums and Challenges

While universal application of artificial intelligence in epigraphy is still much distant, it would be presently befitting to extend some thought to its potential use in Indian epigraphy. Keeping in mind the bewildering diversity of scripts and sounds across the Indian subcontinent, artificial intelligence faces a tough challenge that differently emanates from four sources:

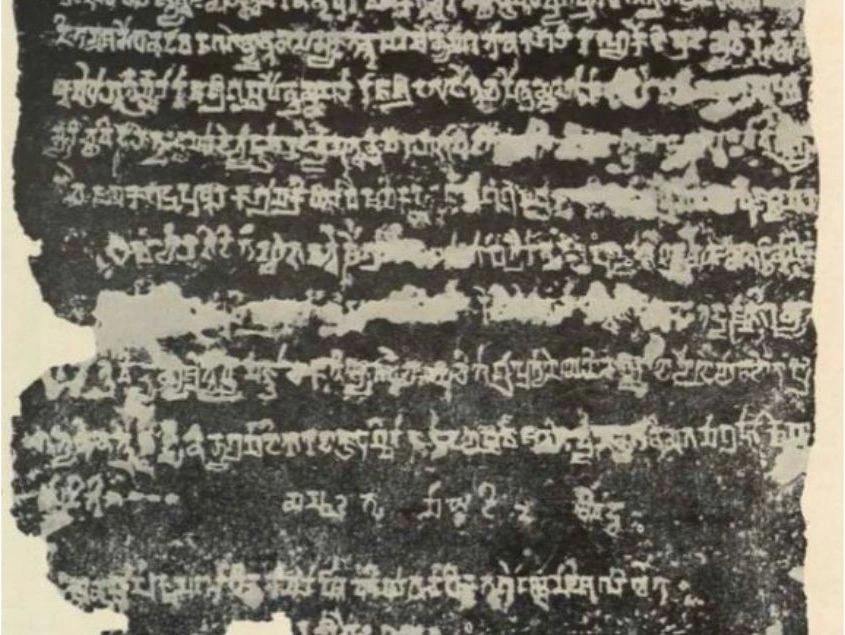

Epigraphical

While the LED (Latin Epigraphic Dataset) corpus, upon which Aeneas presently works, is connected with sturdy materials such as stone and metal, Indic evidence is found even on palm leaves, animal hide, alloyed plates, etc., with varying scales of textual preservation. In addition to fragmentation and effacement, the inscriptional corpus further suffers from weathering and deliberate defacing, while the prevailing socio-cultural context gets invariably impressed on any inscription.

For example, some charters of King Harṣa of Kanauj (c. 606–647 CE), which contain standard proto-Gupta Brahmi in the primary ‘content’ section, end with the king’s signature in highly ornate Siddhamātṝkā script, which perhaps highlights the scribal skills of an accomplished poet-king. Scholars rightly assert that scripts evolve and change in relation to surrounding cultural environs, that too at different paces, a stark contrast especially between urban and rural settings—a stark contrast seen across Indian epigraphy.

Linguistic

Any operating system can utilize embeddings when a sure-shot precedence exists; Indian epigraphy has many words, terms, phrases, and even languages with no universally accepted meaning. Some of these words come from languages with no known records, or are lesser-known dialects of a standard language. Sometimes, misunderstood terms carry the influence of a foreign language, or have a substratum with an entirely different linguistic affiliation. We also encounter perplexing records such as EHS (Epigraphically Hybrid Sanskrit), found in relation to Buddhist contexts, possibly indicating a hybrid typology, a phenomenon that would feel neither alien nor strange once one comes across the Prakrit language with Sanskritic syntax, as seen in Pallava charters.

Logistical

The inscriptional record of India brims with gaps and holes. With each turn of the spade, multiple epigraphs see the light of day, which highlights the need for further exploration of untraveled frontiers. Aeneas works by combining inscriptional record with a particular geo-cultural niche. In the Indian context, even the precisely worded Schism Edict of Aśoka that occurs at Sanchi, Sārnātha, and Kosam carries important differences, which highlights different degrees of administrative focus over scribal matters, something that literally flies in the face of Aeneas’ promised functionality.

Two inscriptions within one geo-cultural niche irreconcilably differ, as seen in neighboring epigraphs of Mihirakula (c. 515–530 CE) and Mihira-Bhoja (c. 832–870 CE), both located at Gwalior Fort. Inscriptional style often changes with the movement of a community. The Hisse-Borala inscription of Devasena (c. 455–480 CE) is perhaps the only Vākāṭaka inscription that refers to a dated reckoning (Śaka year 380 = c. 457–58 CE), which is strongly against standard Vākāṭaka epigraphical traditions, all due to the fact that the patron of the inscription hailed from Gujarat, where usage of the Śaka Era was in vogue. Indian epigraphy abounds with solitary inscriptions of known, relatively less known to completely unknown rulers and individuals, which tersely increases the entropy of epigraphical datasets to unaccountable proportions

Graphical

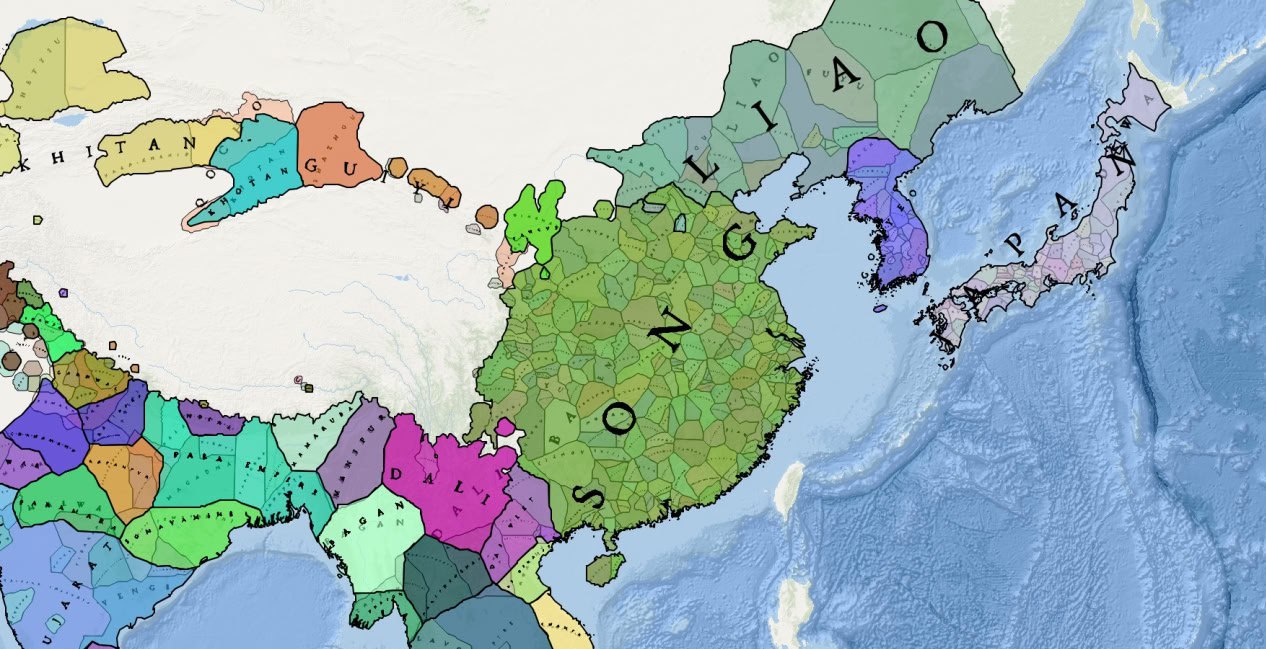

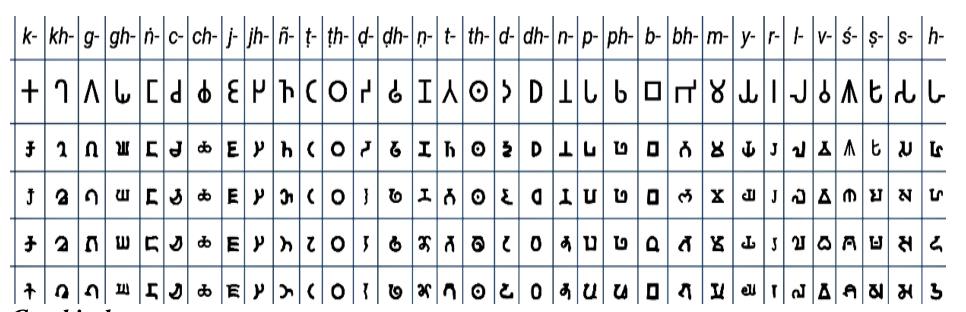

Aeneas is extensively focused on one graphical script—Roman, a limitation that would hopefully be addressed by the research team in upcoming years. However, even a preliminary perusal of the Indian context reveals a rich variety of scripts, with a numerical strength not fully accounted for. Herein, the same script changes with every differing time period (see fig. 2), probably due to change in writing material, scribal traditions, geo-cultural influence, etc.

The graphical challenge is therefore twofold: firstly, a perplexing diversity of scripts makes for a torturous dataset, which would amplify problems related to algorithmic recognition. Secondly, even within the same geography, scripts dynamically change graphical form in no accordance to any order; one cannot necessarily associate graphical change with a particular dynasty or time period; in many cases, older varieties out of nowhere walk side by side with newer graphical styles.

Conclusion

It could be said that, in toto, the use of artificial intelligence in epigraphical studies could act as a Midas touch, but only if its operative mechanisms are taken for what they, in truth, are—as Assael et al. emphatically assert, Aeneas is at present an evolving machine-learning system that should only be considered an indicative tool, and used by epigraphists to ‘show direction, a point to start’ rather than the entire pathway, somewhat akin to how ChatGPT can be wrongly used to write automated essays, or alternately, utilized rightly to refine one’s voice by utilizing its feature of grammatical rectification. Similarly, beginners and novices can utilize Aeneas’ skills to build insightful networks of information, rather than becoming entirely dependent upon its interface.

To conclude, A.I. tools in epigraphy, such as Pythia, Ithaca, and Aeneas, could surely bring newfound vigor in epigraphical endeavors and lead us towards impressive finds, but they have far more to cover and cope with to become established worldwide and deal with other epigraphical traditions, wherein it is likely to face serious challenges to its utility, as exemplified by our discussions above on Indian epigraphy. A greater consideration, however, must be given to the ways we use such a promising technology, whose ultimate aim must be to increase knowledge, rather than distort it through clever contrivance. To ensure that, it is necessary to think if such services are complementary to the efforts and exertions of epigraphists, not as their substitutes.