Death of the Author…Again: Chatbots as Authors

Authorship After Accreditation: AI and the Problem of Authority

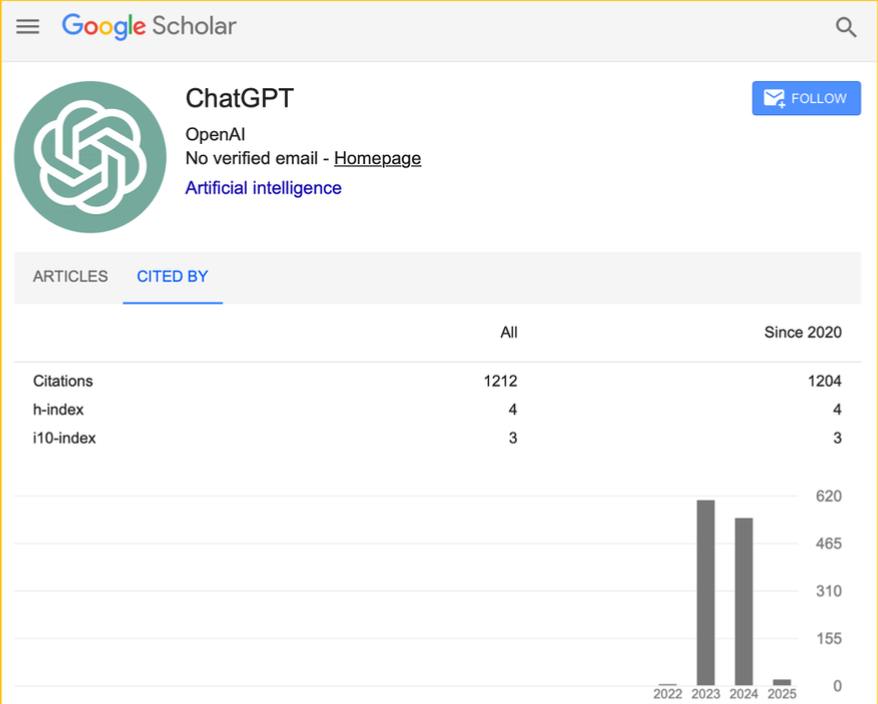

At the beginning of 2025, ChatGPT boasted as many as 1212 all-time citations. But today, there remains no proof of it, nor does it any longer have a Google Scholar profile.

Of course, there persist, as usual, behind-the-scenes decisions taken by shadow players, but the implication of this once gloriously ‘accredited’ profile should be clear to all today. This is where I recall Roland Barthes’s declaration of the “death of the author” and Michel Foucault’s theorization of the “author-function,” which have long shaped debates about textual meaning, interpretation, and ownership.

Neither theorist could have anticipated the emergence of generative AI and its impact on writing. As large language models (LLMs) now produce poetry, essays, translations, and entire narratives, questions that once seemed theoretically safe have gained new urgency. The notion of authorship, already destabilized by poststructuralists, faces fresh challenges in the age of algorithmic writing.

Theoretical Lineages: Barthes, Foucault, and the Death of the Author

Barthes’s essay asserts that writing is “the destruction of every voice,” a process in which the text becomes independent of its creator (Barthes 142). Meaning, he argues, arises in the act of reading rather than in the biography or intentions of the author. Foucault extends this logic by showing that the “author” is not a person but an institutional construct tied to ownership, accountability, and the policing of discourse (Foucault 205). If Barthes killed the author, Foucault buried them.

Yet, AI complicates this obituary. With what may be called AI-écriture, writing is no longer bound to human cognition. LLMs generate text through probabilistic modeling, drawing from vast linguistic corpora to produce work that appears intentional. This raises fundamental questions: Does AI possess authorial intent? Should AI-generated work be treated as genuinely creative? And who, if anyone, owns or is responsible for text generated by a machine? Current publishing practices offer one answer. Journals such as Nature explicitly prohibit granting authorship to AI, noting that authorship requires forms of responsibility that LLMs cannot fulfill. Still, AI writes with increasing fluency and frequency.

Despite ongoing ethical concerns, generative AI has transformed the domain of writing in several beneficial ways. Scholars note that AI tools democratize the writing process by lowering barriers for users who face linguistic or structural challenges (Hu 1781; Jebaselvi et al. 53; Raj et al. 11). AI’s ability to mimic genres and styles allows for experimentation and hybrid forms of storytelling, such as Ross Goodwin’s 1 the Road (Jebaselvi et al. 54). AI-driven literary analysis tools also expand interpretive possibilities. For instance, Raj et al. describe how the Syuzhet Package maps narrative patterns with a level of precision difficult to achieve manually (14). In professional settings, AI accelerates non-creative tasks like copyediting and summarization, freeing human writers to focus on deeper creative work (Mateos-Garcia et al., qtd. in Hu 1783).

Ethical Risks and the Erosion of Authorial Voice

Yet the risks are equally significant, as announced by Bao and Zeng in 2024: Considering a generative AI as a coauthor is a degradation of human dignity, as it implicitly suggests that humans are also reducible to “prompt engineering.” LLMs often produce “hallucinations” or false statements presented as fact, which can mislead inexperienced writers (Jebaselvi et al. 55). The homogenization of writing also looms large, while elsewhere Kreminski warns of a “death of the author” where the writer’s voice thins beneath machine-generated phrasing (48).

Because AI is trained on existing texts, it also raises concerns over plagiarism and intellectual property (Bao and Zeng). Additionally, bias remains an ongoing issue, as models replicate inequalities embedded in their training data (Raj et al. 13). Most of all, Vallor argues that overreliance on AI risks diminishing human self-knowledge and encouraging a dangerous “self-deception” (qtd. in Bao and Zeng). Without doubt, as with all powerful technologies, generative AI may also be misused for misinformation or political manipulation (Jebaselvi et al. 56).

Methodology: Surveying Perceptions of AI-Generated Authorship

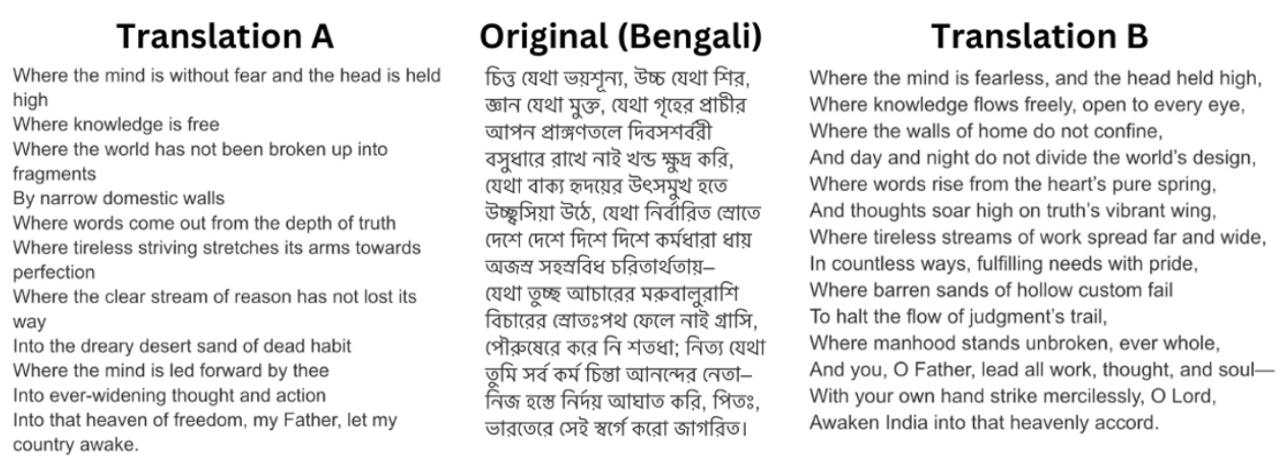

To explore public perceptions of AI authorship, I rolled out a Google Form to present respondents with paired human translations and AI-generated translations in Bengali, Japanese, and Urdu.

Although the sample size was limited (n = 22), the results reveal intriguing patterns. For Nobel laureate Tagore’s poem, respondents were evenly split between the poet’s original translation and ChatGPT’s version!

Likewise, for a Japanese poem by Kaneko Misuzu, 54.5% preferred the poet’s translation, while 45.5% selected ChatGPT’s. In evaluating AI-generated Urdu translations, 59.1% favored the version produced through extensive prompting rather than a single request. When comparing AI-generated poems from three different models, ChatGPT and Andrew Bell’s Poetry custom model tied at 45.5%, with PoemGenerator.io trailing at 9.1%.

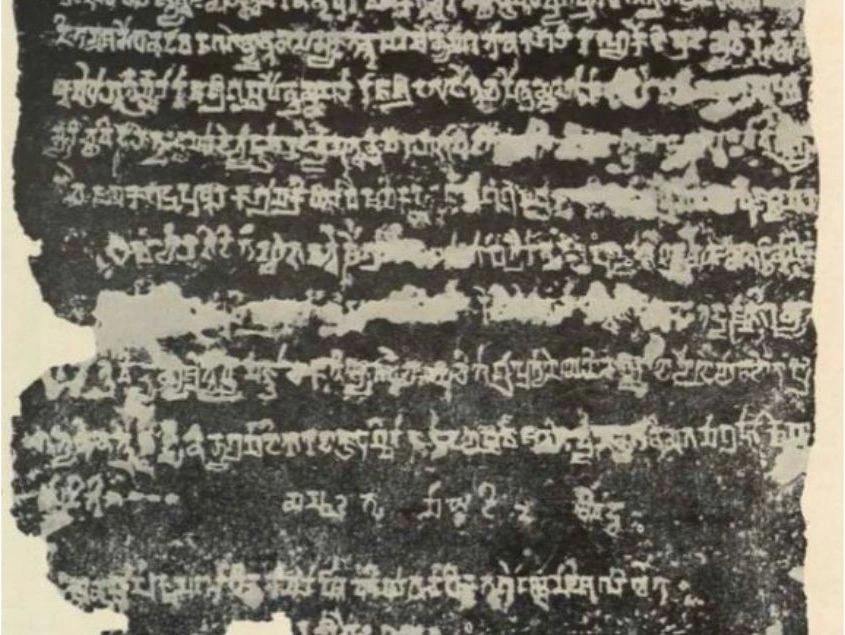

There was also a Burmese poem, the translation for which marked the first of several problems tied to AI translation. Because reliable OCR tools were unavailable, a substantive AI-generated version couldn’t be produced. But the existing human translation still stands as a quiet reminder that human creativity doesn’t crumble just because a machine can’t replicate it.

User behavior mirrored this divide between skepticism and acceptance in answering a series of subjective questions as listed below:

- Have you used AI models or chatbots to generate text for creative or academic purposes?

- Did you ever claim AI-generated text as your original work?

- Did you experience any amount of hesitancy or guilt in doing so? Please give an explanation for your answer.

- Please share your opinion about AI authorship, or your experience using AI models and chatbots, or any other allied subject within this field.

User Attitudes Toward AI-Assisted Writing

A significant majority (77.3%) had used AI for creative or academic writing. Of these, 23.5% acknowledged claiming AI-generated work as their own, while 88.9% reported no guilt in doing so. Some of the responses cited these uses: checking grammar, structuring discussion or answers, explaining complex ideas, “simplifying writing, saving time, and enhancing creativity.” Other responses stated:

“I generally take suggestions from the AI using prompts to engage with the ideas; in that sense, we all refer to past works to come up with new ideas…”

“For me, AI has intelligence, but not a ‘creative intelligence’. Because it is only able to generate those things that are already available to the server; however, creativity is something that needs ‘self’. In short, I can say ‘self-awareness results in creativity.’”

“I have purposefully used AI to meet college assignment deadlines. Essays, diagrams, ppts, etc. My peers knew. No teacher questioned, thus never did I claim them to be my creations. But yes, they were very much there.”

“Because the inputs given to the chatbots are solely exclusive to the person who is entering it. Thus, the results generated are also unique.”

Conclusion

These findings, I assert, suggest that AI has not replaced human authorship but is reshaping it. As Huargues notes, technological change has never extinguished humanity’s drive to create; rather, it alters the forms creativity takes (1781). Kreminski, similarly, envisions a future in which AI tools create an “abundance of the author,” amplifying human intentionality by offering perspectives and revisions beyond the writer’s individual capacity (50). The challenge, however, lies in building systems grounded in transparency, accountability, and ethical literacy. Scholars stress the importance of educating writers, editors, and digital humanists to navigate AI responsibly (Raj et al. 15).

The author is not so much dead as multiplied, and authorship will necessarily continue to evolve, shaped not by nostalgic attachment to singular genius but by ongoing negotiation between technological possibility and human values. Whether this future becomes empowering or extractive depends entirely on how writers, institutions, and policymakers respond.