Mapping History with AI: Highlights from the Historica.org Conference Q&A

On December 2, 2025, the Historica team presented the latest stage of its project at an academic seminar at the University of Cambridge. The seminar brought together historians, digital humanists, and researchers to discuss the project’s progress and future goals.

The event opened with introductory remarks about the origins of the Historica Foundation and its founder, Alexander Tsikhilov, who stood alongside the chief strategist, Fedor Ragin, and the AI specialist and Chief Technology Officer, Nikita Balabanov.

Two years earlier, an initial seminar at Cambridge University had presented only the conceptual foundations. This time, the team returned with a working proof of concept and a live demonstration by lead developer Nikita Balabanov.

After the presentation, the session moved into an extended Q&A with the audience. Below is a summary of the main questions raised and the team’s responses.

What is Historica.org trying to build?

The core idea behind Historica is to create a tool for generating dynamic historical maps from textual sources via creating formatted datasets using AI.

Traditional historical mapping projects rely on manually curated datasets built by teams of historians – a process that is extremely slow, expensive and often limited to political borders at a single point in time.

Historica takes a different approach:

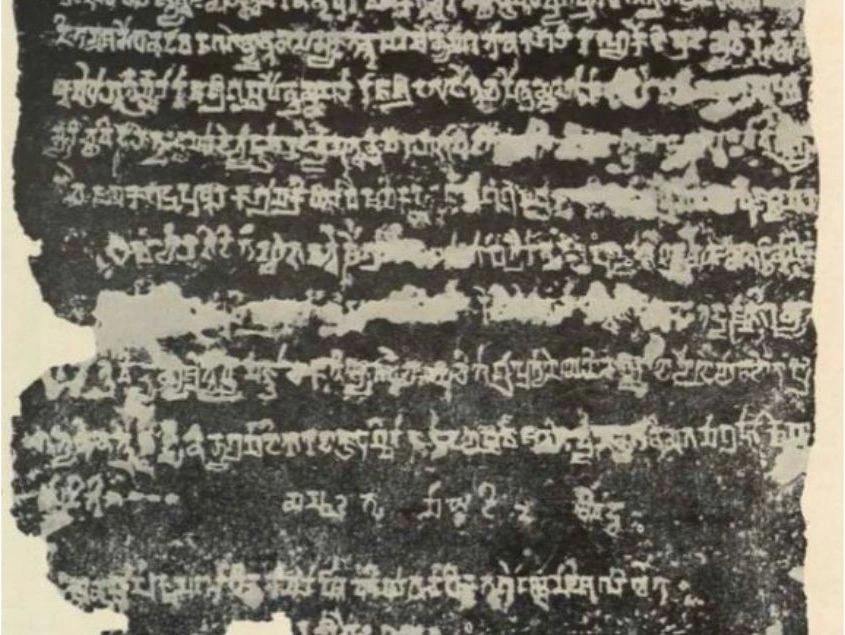

- AI models are used only to parse historical texts (articles, papers, books, web sources) in different languages and extract structured facts about places, dates, political entities and events.

- These facts are stored in a transparent, simple to correct or edit, verifiable data format that always links back to the original source.

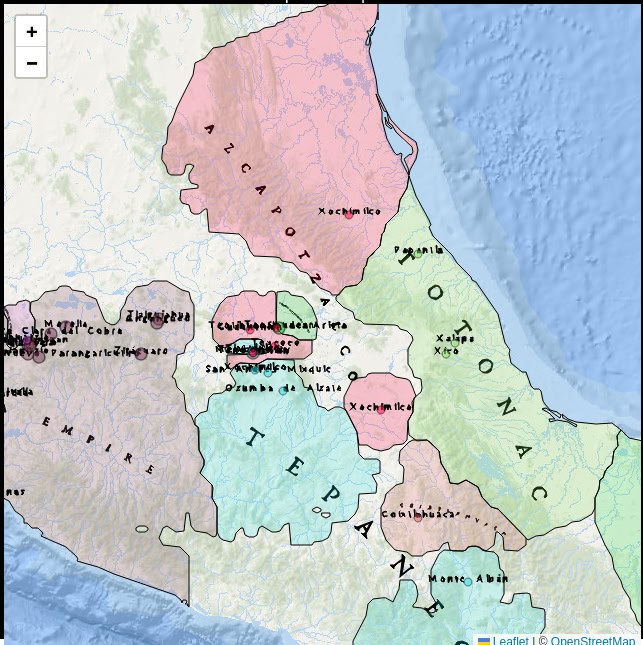

- A fully deterministic “map builder” then turns this structured data into maps using a mathematical model of “areas of influence”, taking geographical features of Earth into account.

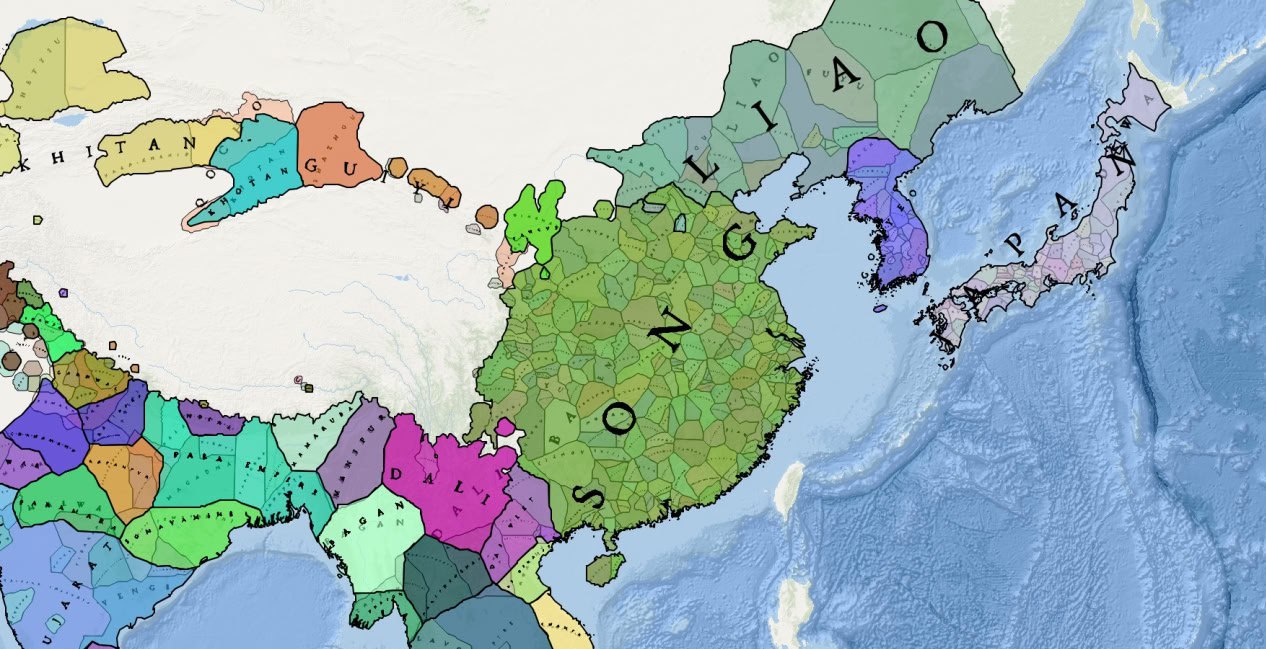

The result is not a single “definitive” historical map, but a flexible system that can be used to generate many different maps and layers, depending on the data and assumptions chosen by the user.

Are the maps “authored” by users?

One of the first questions from the floor was about authorship:

Does every map become “Nikita’s map” or “Alexander’s map”? Is each one essentially a user-authored interpretation?

The team explained that there are two levels of mapping:

- Base maps

- Historica maintains a growing base dataset built from open sources and widely accepted (“consensus”) historical knowledge.

- From this base data, the platform generates maps that are the same for every visitor – for example, geopolitical maps from the year 1000 to 2024.

- User-specific maps

- Researchers and other users can upload their own datasets (for example, from a research project, thesis, or archive).

- Using the same tools, they can build private maps that reflect their selected sources, interpretations and research questions.

- These user maps can remain private, or – if the user explicitly agrees – selected data can be added to the base dataset.

In that sense, yes, there can be “your map,” but it exists alongside shared base maps, and the system always keeps track of the source of each piece of data.

How are conflicting sources or interpretations handled?

Another major question concerned historical disagreement:

When sources disagree—for example, about early medieval borders—who decides which version appears on the map? Is this left to AI?

The answer was clear: AI does not “judge” history in this project. Historica is unbiased.

- Every historical record in the system is linked to one or more sources, and the tool keeps track of this provenance.

- In cases of disagreement, users can choose which sources to rely on or how to weigh them.

- For base datasets, the team aims to reflect widely accepted consensus (for example, that London has been under English/British rule in modern centuries), while leaving room for more precise or alternative interpretations at the user level.

In future versions, the team plans to offer tools that help users see where sources conflict and explore different scenarios, but the responsibility for interpretation will remain with human researchers.

Why do borders change when a new point is added?

One audience member asked about a live demo of a Sumerian map:

When you added a new “test town,” the borders of neighboring entities changed. Where do these new borders come from?

Nikita Balabanov explained that the map builder is a mathematical model, not an AI model:

- Each point (a city, settlement, or site) is assigned an “area of influence” representing the territory historically associated with its polity.

- These areas of influence change over time and interact with each other—whe two entities are close, their zones push against each other to form a boundary.

- Geographical features (mountains, deserts, seas, and major rivers) are also factored in, because they have historically influenced political and cultural boundaries.

The model is deterministic: given the same data, it will always produce the same map. Users can also adjust parameters such as the radius of influence, or manually add many small points along straight borders when modelling modern, artificially drawn boundaries.

How will users navigate such a complex system? (Indexes and layers)

Another important theme was navigation and indexing:

Historical work depends on indexes and ways to navigate material. How will users find what they need in such a multi-dimensional environment?

Here the team highlighted the concept of layers:

- Users will be able to create and select different layers: political borders, administrative divisions, religions, plagues, migrations, trade routes, cultural phenomena, and more.

- Layers can be combined, compared or switched on and off – for example, overlaying plague spread with political boundaries or bird migration with climate data.

- In the longer term, Historica plans to develop better indexing and navigation tools so users can explore themes (e.g. “economic history”, “linguistic changes”) more like an index in a book.

The team acknowledged that designing intuitive navigation for such rich, multi-layered data is a core challenge and welcomed further ideas from the academic community.

What exactly does the AI do—and not do?

Several questions focused on the precise role of AI:

Is AI guessing boundaries or “filling in” history? How is it different from students drawing maps by hand?

The team stressed that AI is used in a clearly defined way:

- AI models are applied as parsers: they read large volumes of textual sources (articles, books, web pages) and convert them into structured records (place, date, entity, relationship, source).

- The map building itself does not rely on AI – that step uses algorithms designed by the team to approximate historical areas of influence.

- Because every record links back to a source, users can always inspect, correct or replace AI-generated data.

In parallel, the team plans to develop a standalone parsing tool so historians can use it to extract data from their own documents into whichever format they need – not only for mapping.

Can Historica be used beyond political maps?

Several questions explored broader possibilities:

Could this tool be used to map trade routes, manuscript journeys, migration patterns, or economic data?

The answer was yes, it is possible, but since there are limitless topics that could be explored, Historica is not planning on expanding in that direction right now.

The team emphasized that we cannot personally build maps for every possible topic; instead, our goal is to provide a generic, flexible tool that researchers and institutions can adapt to their own questions.

What about data sources, copyright, and partnerships?

One audience member asked how far the team intends to expand its data sources and how copyright is handled.

At this stage:

- The project is still at an MVP / proof-of-concept phase.

- The team experimented with parsing large textual datasets, including Wikipedia content, but found it to be very demanding in terms of time and resources. In addition, copyright considerations require a very cautious approach.

- Due to ongoing debates about how AI systems handle copyrighted material, the team will focus on using datasets that are public, properly licensed, or fully cleared for production use. Also, we don’t use any data to train any AI models.

For private research use, individual users will be able to upload and work with their own sources inside their own accounts:

- These private datasets are intended to remain visible only to the user, unless they explicitly choose to share or contribute parts of them.

In the longer term, once the technology is stable, the team hopes to work with libraries, archives, and research institutions to license and integrate richer datasets in a way that respects copyright and builds trust.

Key Insights from the Discussion

The Q&A surfaced several important themes for the future development of Historica.org:

- Trust and transparency are central: users must be able to see where data came from and how maps were constructed.

- Human interpretation remains essential: AI assists with parsing and scaling, but does not replace historians’ judgment.

- Tools must be shaped by real research needs: the team is actively seeking feedback on which features, layers and navigation methods are most valuable.

- Partnerships with the academic community will be crucial for sourcing data, testing use cases and refining the platform.

The project’s ambition is clear: not to create a short-lived “historical toy”, but to build a serious, flexible instrument for the academic world. The Q&A session in Cambridge showed both how far the team has come and how much exciting work still lies ahead.

If you want to dive deeper, watch the full seminar video