History, Data, and the Role of AI in Research

Introduction

History is unique as a science. It is, at its core, data and its interpretations. Sometimes it looks like a coherent story, sometimes not. Other scientific fields often operate with standardized data, measurements, and formats. History, however, either lacks such data standards or sees them constantly questioned by other historians.

For example, just the classification of European swords of the early Middle Ages has at least two different systems of classifications—by Oakeshott and by Kirpichnikov. And this is just one of many examples.

It’s often hard to gather together data from different sources: on a base level, all archaeological data requires professional interpretation and often comparing to other data or interpretation from similar archaeological sites.

At a broader level, the challenge remains the same: data from multiple large-scale research articles are often presented in disparate formats, necessitating a lengthy and resource-intensive process of merging. Whichever part of historical science we turn to, the same issues are rooted in the informal nature of human communication.

Here, AI emerges as a tool that can help us build interfaces or unifications of historical data at a low level. AI comes with real limitations and is often viewed with suspicion by scientists—and that tension is precisely what this article explores.

AI as a tool

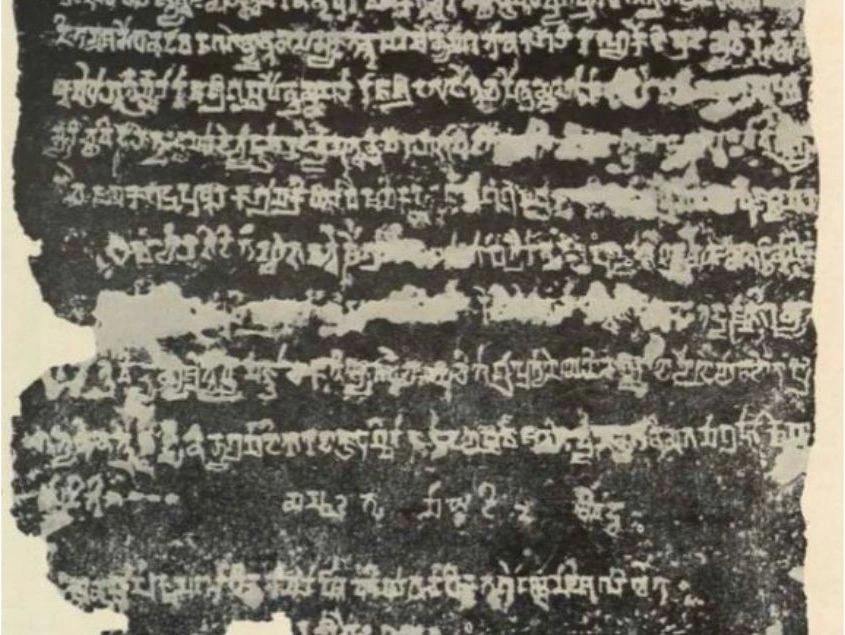

Of course, AI is not a magical solution to all problems, despite what some boldly claim. And AI is not an autonomous actor capable of replacing real scientists or researchers. As a tool, AI is not so different from the printing press, from paper, or—if we allow ourselves some irony—from clay tablets.

The current state of AI is at its local optimum—big, very intelligent-looking statistical models. Until a fundamental revolution in the concept of AI occurs, improvements to existing AI models are likely to remain incremental.

Once this is clarified, we can begin discussing the applications and limitations of AI in history and science. First, we need to make it clear that using AI as a decision tool serves little purpose. As a statistical model, AI exhibits what is commonly referred to as the 'average problem.' Because AI responses are based on a given amount of data, they are typically an average of all the data used to train the model. What if the training dataset for the model contains some distorted data on a topic that developers of these models have a special interest in?

This and the fact that training datasets are usually kept secret makes AI very untrustworthy, especially with data of any political value in it. Moreover, LLM models tend to reinforce connections between similar data, so these small changes in datasets can lead to unpredictable distortions of responses of the model.

Even taking this into account, AI performs remarkably well on narrowly defined tasks. The tasks that cannot be solved by usual linear algorithms. For example, parse and extract data from articles and papers, and transform data from different sources to one single format, or respond to small, atomized questions to check the correctness of data or find mutually exclusive elements in data. This is what makes AI great for historical research.

Now humanity cannot just gather and store incredible amounts of data about all sorts of things—from historical sites, property owners, and populations to climate and other contexts that have surrounded humanity throughout history. What we lacked only 20 years ago was a tool to standardize and process it. Of course, errors can still occur, so any research that heavily relies on AI must be supported by robust evidence from non-AI sources.

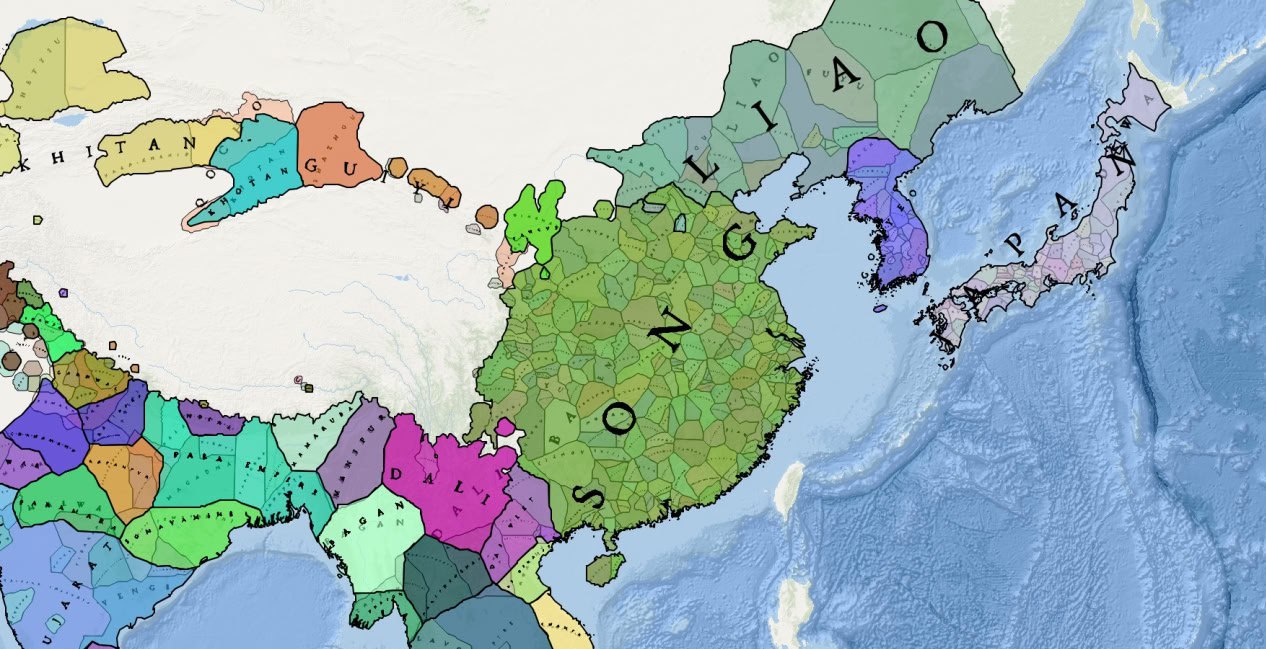

In our work at Historica, AI is not used to create a vague reflection or model of human history but to gather data, build interfaces, and help us connect different sources of data.

No existing model truly comprehends the concepts of history, human behavior, or spatial representations such as maps. We build historical maps based not only on proximity to points of interest but also on the Earth's geographical attributes. Mountains were typically natural barriers for ancient civilizations, and the same applies to deserts and jungles. For such features, we do not use AI, relying instead on straightforward linear mathematical methods.

The Future

Perhaps one day, with the development of true strong AI, it will be possible to have a single AI entity capable not only of containing the entirety of human history but also of actively processing it. Such an AI could discern hidden correlations between historical processes—not just related to climate, but across a broader spectrum of planetary and extra-planetary phenomena: from climate cycles and solar activity to biological changes, such as the emergence of new diseases or the spread of species, whether natural or artificial.

It could generate theories and compare different interpretations within the full context of history, without the limitations of the human brain. However, the existence of such AI remains uncertain, particularly in the near future.